I was recently conducting research for a talk on Cornish Midsummer customs when I had cause to read through the book Observations on the Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall by William Borlase, published in 1754. Many of the Midsummer customs in West Penwith involve fire and bonfires, so my eyebrows were raised by the following quote:

In Cornwall we have Karn-Gollewa, that is, the Karn of Lights; and Karn Leskyz, (the Karn of burnings), both call’d so probably from the Druid Fires kindled on those Karns. Karn Leskyz has some things which deserve a particular description.

Observations on the Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall by William Borlase, 1754, p.131.

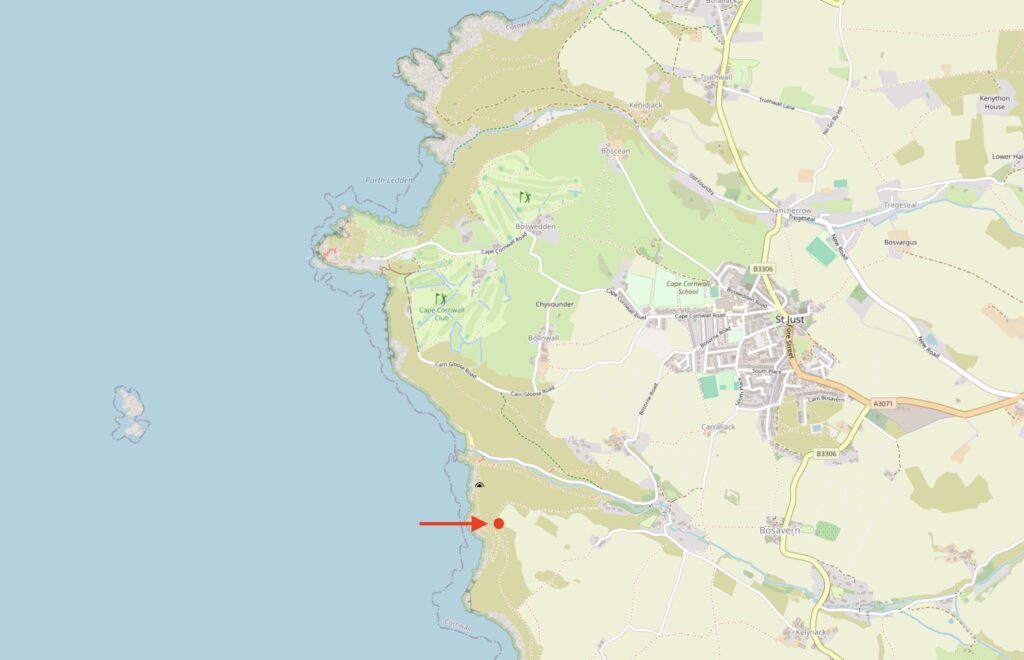

“Karn Leskyz” is spelt “Carn Leskys” today and can be easily spotted on a modern Ordnance Survey map south-west of St Just, and just south of Porth Nanven.

Borlase goes on to describe what could be a stone at Carn Leskys containing natural solution hollows and potentially some cup marks, making this stone of interest to archaeologists. A quick check of the Cornwall Historic Environment Record (HER) didn’t show any record of any rock art in this immediate area.

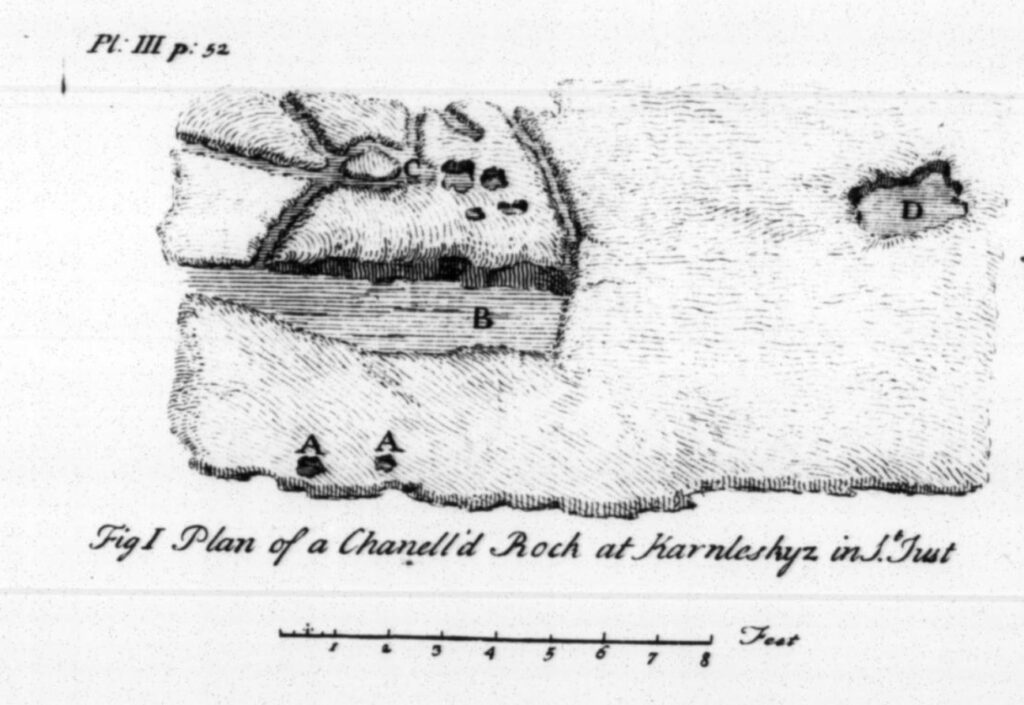

He went on to describe the stone, and provide a sketch plan.

Since I know the area around Carn Leskys reasonably well, I thought that I must go and search for the stone. J. O. Halliwell in his 1861 Rambles in Western Cornwall suggested that he couldn’t find it saying that “these stones have been destroyed by mining operations” (Halliwell 1861: 126), but it would be good to confirm this.

Borlase’s description reads:

“It is a large ridge of rocks, descending from a very high hill in the tenement of Lechau (St. Just.) to the sea, and consisting of several groupes, in the highest of which there is one small bason, about 18 inches diameter, it’s sides about six inches deep, (Plate III. fig. 1. D); about five paces to the left of which, on the same Karn, whose surface is plan’d or flat, is an oblong cavity five feet long, (B), and in the shelving sides of the rocks adjoyning on both sides, are several little grooves or channels about two inches wide, and as many deep, cut into the surface, and running by the side of one another in a vernacular direction (C); they are certainly artificial, but what use to assign them I know not, unless we suppose them the divinatory channels, into which, as the blood of the unhappy victim flow’d, either to the West or East, North or South, freely or languidly, into few or many of these ducts, so the fate of the nation, the army, or the sacrificing enquirer was accordingly predicted to be happy or unhappy*. There are also on the East side of the oblong cavity before mention’d, and on the same Karn, two small, exactly round holes sunk into the top of the rock; some others of like kind may be seen intermix’d with the little ducts; they are about four inches diameter, and three deep (A A A).“

Locating the range of rocks called Carn Leskys was simple. However, the number of mineshafts – some collared and some not – close to the path on both the inland and seaward sides meant that searching the undergrowth wasn’t safe to do as part of a casual search.

But soon enough the path opened up and I came to an open view of the sea. And some flat granite rocks with some interesting features.

Unless Borlase’s plan was truly very bad indeed, perhaps Halliwell was right. Although it is quite possible that Borlase’s plan was drawn from memory at a later date. However, the rock closest to the cliff edge seemed to have some interesting features. Some definitely natural, and others that definitely seemed to be deliberately shaped by human hands. It contained all of the features mentioned by Borlase in his description.

A large solution hollow similar to Borlase’s (a scale marker can be seen at the bottom of the basin) about 182cm (or 6 feet) in width is visible and its shape wasn’t unlike his sketch.

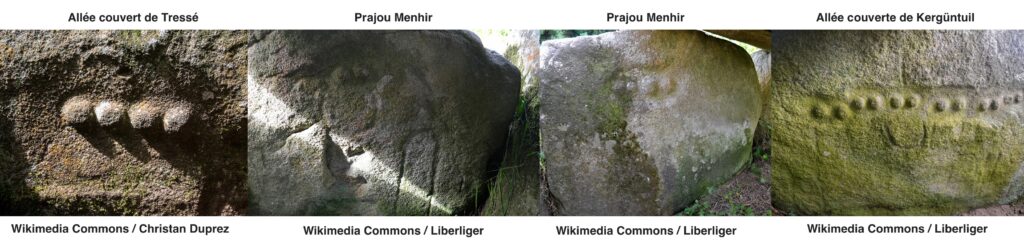

On the seaward side, above the solution hollow, is a curiously-shaped stone. The natural fissures have eroded away to create a ‘barley twist’ pattern along the edge; perhaps originally the location of large feldspars. There are some circular depressions that could be cup marks. There are plenty of ‘features’ that are completely natural. But what interested me most were two circular features similar to those interpreted as ‘breasts’ found in, or as part of, passage tombs in Brittany, France.

Framed by a trapezoidal boundary, the motifs are facing inland, and as such have a small degree of shelter from the prevailing westerly winds off the sea. This position is likely to have contributed to their survival.

These images show comparison ‘breast’ motifs from allée couverte de Tressé, Prajou-Menhir, and allée couverte de Kergüntuil, in Brittany, France.

I have also made a basic 3D scan of Carn Leskys. This is best viewed as a Gaussian Splat where you can appreciate the monument’s setting, or as a mesh via Sketchfab where you can view the stone with annotations and alter the lighting.

Clearly much more work and verification is required at Carn Leskys. When I visited the lichens were covering the base of the trapezoid enclosure which contains the motifs. In Cornish granitic rock art there is rarely much evidence for pecking/working the stone, mainly due to the coarse nature of the granite and their exposed locations. The Breton examples are usually within a megalithic structure (tombs) which have given degrees of protection from erosion along with being carved into finer grained stone.

This is the second set of breast motifs that I have found in Cornwall, with the first being at Boscawen-Ûn stone circle in 2015, alongside my reinterpretation of the axe carvings on the central stone as feet. The breast carvings are about 500mm above the feet.

This is an area relatively (for Cornwall) rich in rock art. In 2021 I also discovered a large cup marked stone at Nanjulian 1.3km to the south of Carn Leskys. Many other cup marked stones, and stones with shallow channels and linear features can be found within a few miles.

Clearly this is now a good time for a renewed effort to survey and collate all that we know about these sites, perhaps in a similar way to Scotland’s Rock Art Project (ScRAP).

This post will be updated as I study this stone further.