I have recently acquired a structured light 3D scanner (SLS) to complement my usual photogrammetry methodology. I have used several structured light scanners in the past, which have yielded incredible results but were costly to hire and occasional hire precludes being able to become deeply familiar with the software and techniques. In the past 4-5 years several ‘prosumer’ SLS systems have come on the market but I have long resisted, seeing only relatively poor results. However, competition between these new 3D scanner manufacturers has seen a great deal of innovation in the past few years resulting in some promising hardware. This year felt like the right time to buy one and try it out.

Whilst photogrammetry will remain my capture method of preference, SLS does have some advantages (and disadvantages) for 3D scanning in a heritage context. Primarily, manufacturers (decent ones, at least) publish their resolution, accuracy and precision measurements. This means that, assuming the scanner performs to these tolerances, when scanning an object or monument one can be sure that data is being captured at the required level of detail, and that the metric data will be of the required level of accuracy. For example, a feature measuring 100mm will measure 100mm (+/- the stated accuracy, e.g. 0.05mm) when measured on the 3D scan. This is much more complex to state when using photogrammetry, as so many factors can affect the resolution and accuracy of the data (density of photo coverage, sensor noise, lighting conditions, dynamic range etc).

SLS has its disadvantages. Often the field of view is narrow, which when scanning a larger monument (like a rock art panel) could mean 250x250mm square field of view. Scanning is slow, moving this small window around the subject, potentially whilst tethered to a laptop which provides the live view of the data. This must be looked at whilst scanning to ensure that the subject has had complete coverage. It can feel a bit like painting a large uneven wall with a one-inch paintbrush. But! It is very easy to check that all areas that you need have been scanned before leaving site. Photogrammetry alignment can take many hours with hundreds of high-resolution (30+ megapixel) photos. Discovering – when back in the office or lab – that not enough photos have been taken of a particular area is a common risk, meaning that planning a photogrammetric survey can be time consuming.

The size of the scanner also matters. Some are aimed at large objects, some medium, and others at small to tiny objects. There is no scanner that will do it all much the same as in the photographic world where usually three lenses or more are required to cover macro, wide, medium and telephoto focal lengths. Any scanner that will ‘do it all’ will have made compromises that will make themselves known fairly quickly. My scanner, a Revopoint Range, is suitable for objects like memorial panels, bench ends, and maybe up to a 2m high standing stone or cross. The same company makes scanners for medium and small objects as well, all with different sets of resolution, accuracy, precision etc. However, there is a large amount of crossover. I have scanned some small (200mm) statues perfectly well, although the level of detail isn’t what I’d like, and I stuck with photogrammetry for that one.

Structured light scanners are generally terrible for capturing colour. They always have been and still are. Examples of colour textures that I have seen from the latest summer 2025 scanners, lauded as ‘incredible true-to-life colour’ – aren’t. They’re muted, mushy, and only indicative at best. Photogrammetry will beat SLS for colour every time for years to come, I suspect. If colour doesn’t matter, which it often doesn’t when undertaking analytical scanning (to enhance surface features, take cross-sections etc), then SLS can be a very quick way to 3D scan within a set of defined tolerances.

Another disadvantage for archaeologists is that many structured light scanners can also perform poorly in bright sunny lighting conditions. Their (often Near Infrared – NIR) projectors can be easily overwhelmed by bright daylight and infrared energy from sunlight. When choosing a scanner, look for “outdoors scanning” as a specific feature.

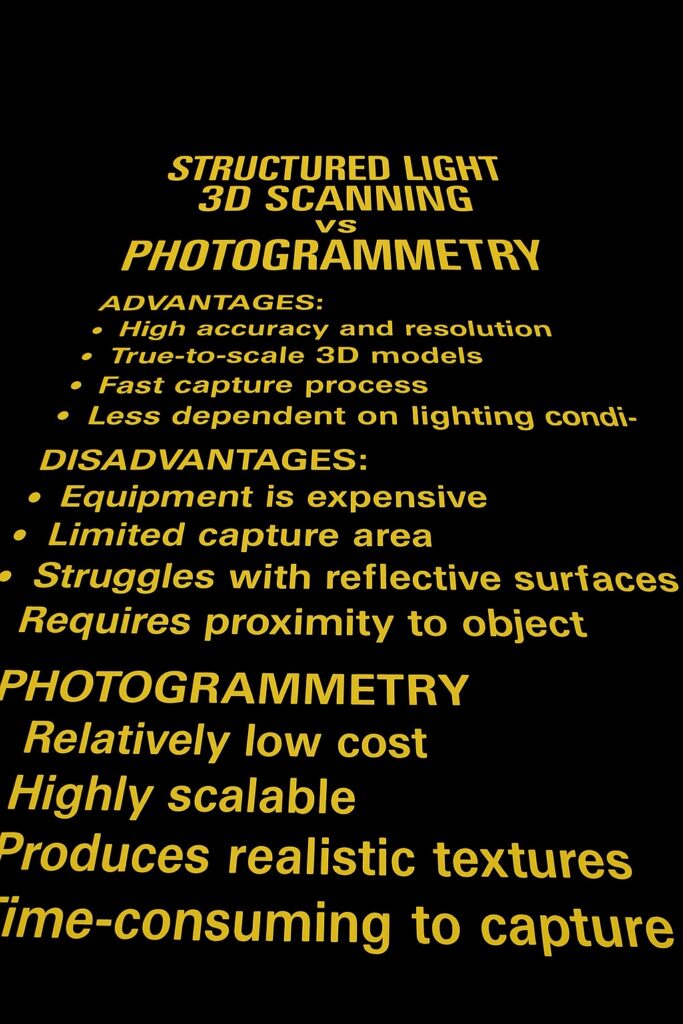

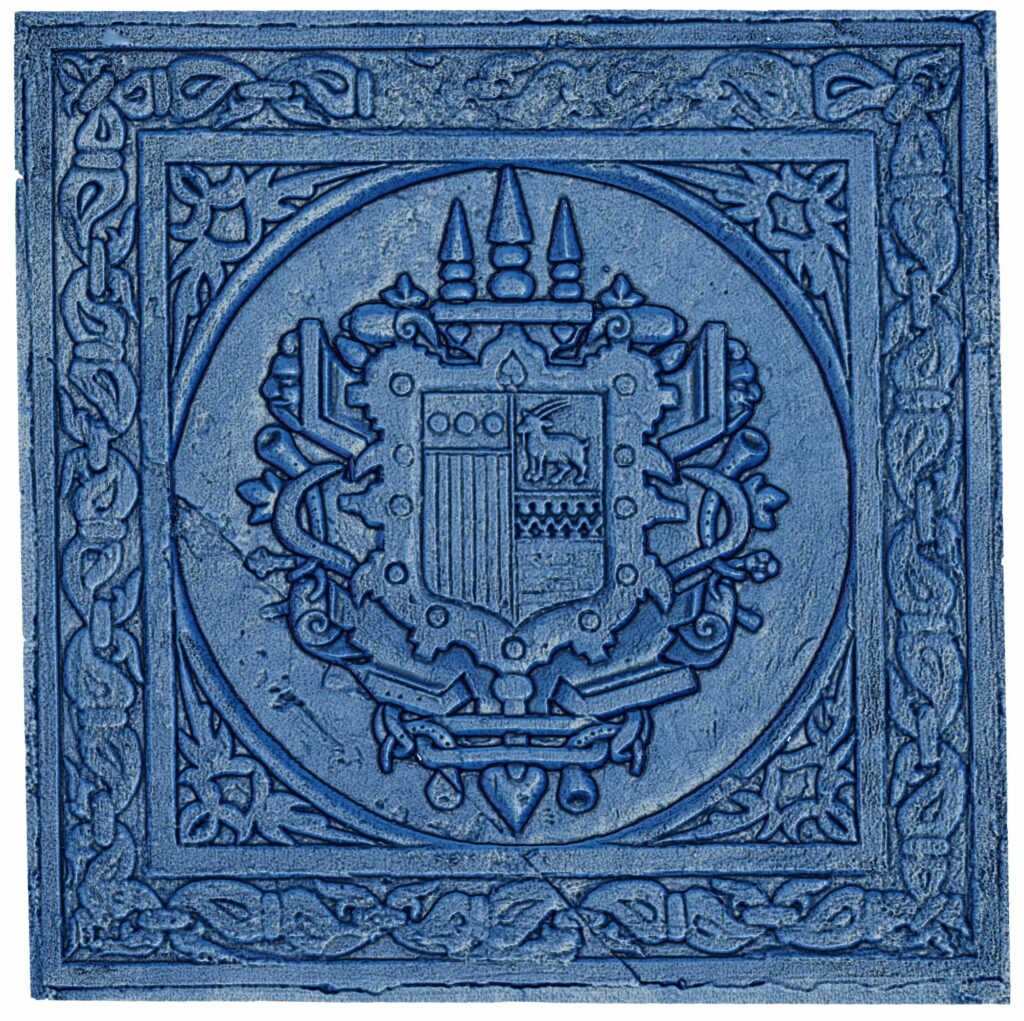

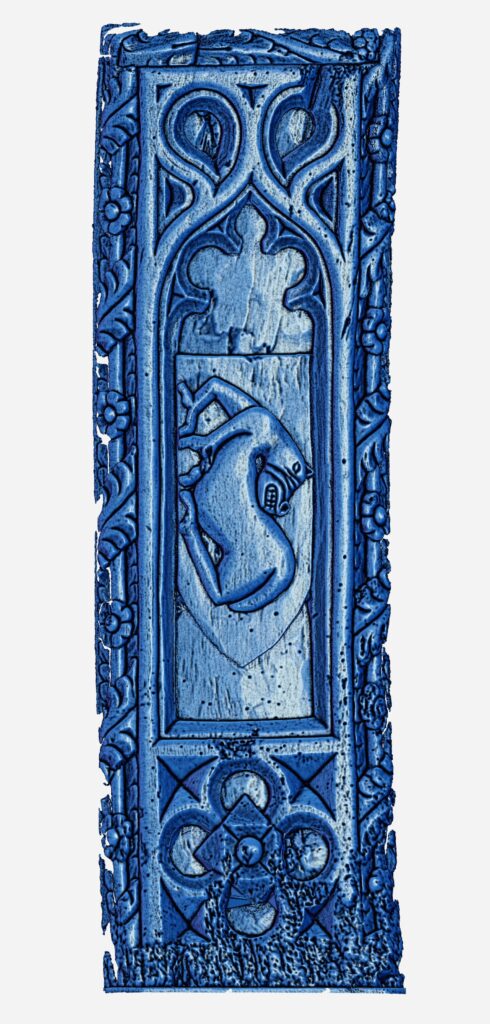

I started to compile a large list of photogrammetry vs SLS but was soon apparent that it would end up like the Star Wars ‘opening crawl’ background story. So here’s a few images of some of the 3D scans I made whilst at St Mawgan and St Nicholas church in St Mawgan (Lannhernow), Cornwall. All data was processed into a high resolution point cloud on site and inspected before leaving. Scan resolution was 0.3mm on a scanner with a claimed accuracy of 0.3mm and precision of 0.1mm (Accuracy = How correct is the scan compared to the real object. Precision = How repeatable are the results?).

Beavers appear in church carvings because they carried strong moral and symbolic meaning in the Middle Ages. Bestiaries (medieval animal encyclopaedias) described the beaver as a symbol of chastity and Christian virtue: when pursued by hunters, it was said to bite off its own testicles, the part most desired, and escape – thus representing self-control and sacrifice to preserve life. Carvings like this one reminded worshippers of moral lessons, linking the natural world with Christian teaching.

These samples, mainly from St Mawgan, show how well the new generation of basic SLS scanners performs in a heritage context. The accuracy and precision might not be good enough for engineering use, but the sub-millimetre resolution and accuracy are certainly more than adequate for archaeological recording.

As with all types of 3D scanner, it is important to conduct your own tests to check the manufacturer claims in terms of accuracy. Use callipers and steel rulers and take diagnostic measurements to test against the 3D scan of the same object. Be especially careful with scanning larger objects – compound errors can grow and grow.

There are many ways to enhance and present 3D data. Get in touch if you’d like my consultancy support, or if you’d like me to carry out the scanning for you.