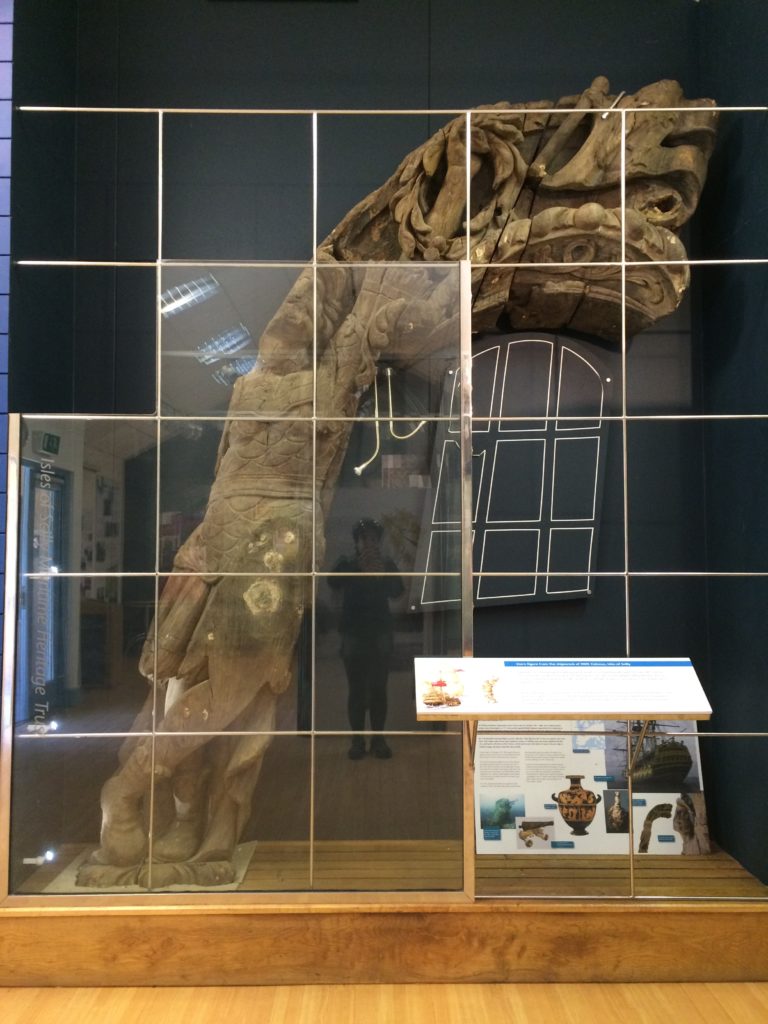

In early 2022 we were asked by Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Maritime Archaeology Society (CISMAS) if we could help them with an intriguing project. In the small museum on the island of Tresco, Isles of Scilly, is a large 3.5m high wooden carving from the stern (back) of HMS Colossus which was wrecked in 1798.

After its discovery, the stern carving was transported to the Mary Rose Trust in Portsmouth for conservation. During its stay, the carving was 3D laser scanned by reality capture pioneers Archaeoptics Ltd in 2006. Their scan, accurate to less than a millimetre was exceptional. However, due to the limitations of the technology at the time, and the amount of reflective water in and around the tank, some parts physically couldn’t be scanned, including one side (which was simply plain unadorned wood) as they were simply too heavy to move and turn over.

As so often with 3D scanning projects, the data was archived and nothing was done with it. This is often by design – if a scan is accurate enough the data is a great record of the condition of the subject.

Fixing holes

In 2021, Kevin Camidge of CISMAS began writing a book on HMS Colossus. He asked us to review the laser scan data to help produce some illustrations. We took the original data from Archaeoptics which had some holes and with their permission began to do some cosmetic work to the 3D model.

Since the remit of the project was to essentially fill in the blanks (the original scan being excellent) we set to work to provide a ‘watertight’ (no pun intended) model which could be digitally illuminated and rendered for illustration.

Some of the holes in the data were tricky to do, so we had to create a ‘scaffolding’. Automatic hole filling in many 3D packages is only much use for simple holes. Here we needed to create a whole new surface that continued the shape of the surface.

We also reattached his (badly damaged) knee, which had become detached and was scanned separately.

Adding colour

Once this was completed, we had some long discussions with CISMAS about the next stages. We also talked about the original colours that might have been used. Some traces of pigment survived and were photographed in-situ before conservation. We had just created the perfect opportunity to try this out and restore some colour to what is now a very brown carved piece of wood.

Based on the photos of the pigment traces (and assumptions about their chemical degradation in seawater) we cross-referenced them against some contemporary paintings. It seemed sensible to assume that whilst the quality of the carving was superb, full of detail, and doubtless executed by one of the best woodworkers of the time, the colour palette was probably quite simple.

Given that the stern of a ship is mainly going to be seen at a distance, as contemporary paintings (although not of Colossus) show, the colours were probably used to create a simple contrast. Against a very dark blue background the details of the character would have been picked out in a gold-like yellow/orange. The letter ‘G’ (for King George) on the flag is likely to have been picked out in the background colour so that it could be easily seen.

Painting in 3D can be tricky. The software is complex, and the very navigation of turning the model as you paint can take a while to get used to. We hadn’t tried doing this before, so the learning curve was steep to begin with.

Going mobile

In looking around at best practice examples of mesh painting, I came across some new ways of doing this using an iPad and Apple Pencil. Use your left hand to navigate and your right hand to paint. The approach went well.

Using the apps Nomad Sculpt for lighting and final fixes to the mesh, and Procreate for the 3D painting we were able to complete the task fairly quickly. Their simple and novel interfaces were refreshing after battling their heavyweight desktop counterparts (which are still absolutely necessary for complex/demanding tasks). We could quickly add lighting and polish the images for publication.

Procreate allowed a lot of creative options, and so rather than have the colours clinically ‘clean’ I added grime and dirt so that it looked as it might have before the Colossus sank.

Compare this back to the brown wood that you see today when you see the original back on the island of Tresco. This project shows just how many uses there can be for what can (and has) been viewed as boring 3D survey data.

Have you got any old 3D scan data that you would like to explore the potential of new uses for it, like digital painting? Contact us and let us know.